Trapped in a swipe loop?

One of the questions that has always bothered me is: “Are existing dating apps creating unhealthy behaviours, such as swipe addiction and ghosting, or are they simply escalating the patterns that already existed in human relationships with systemic design?” Some degree of ghosting or dating burnout exists on these apps; however, the systemic design of these dating apps accelerates and magnifies these tendencies. Dating apps thus do not merely reflect natural novelty-seeking tendencies but intensify them through design.

While the impulse to seek novelty is natural, these apps exploit it by designing pathways that channel these impulses into endless swiping without resolution and escalating superficiality over deeper bonds and detachment over a larger scale. Zuboff [1] argues in her broader theory of surveillance capitalism that digital platforms aim to maximise user engagement for profit, often harming individual well-being. Dating apps thus serve a dual function: they offer the prospect of connection while also creating scarcity, novelty and frustration, ensuring users remain active and dependent.

The dopamine-driven swiping loop: Addiction hidden in algorithmic design

The swipe mechanism on dating apps sets up feedback cycles that trigger dopamine release, reinforcing compulsive use. Ironically, while users seek connections, this loop increases loneliness and anxiety. It keeps users in a state of hope, craving validation and connection. Importantly, the algorithms are designed to intentionally keep the users starved, preventing them from easily finding their people or a long term relationship. While the stated purpose of these applications is to create connection, the loop often produces the opposite result: loneliness, anxiety and diminished trust in others. Existing dating apps are not neutral technologies; their algorithms are optimised for engagement, not well being. This optimisation manifests in design choices that withhold matches to sustain hope, prioritise superficial traits over deeper compatibility and perpetuate user reliance on the platform.

Reinforcement and unpredictable rewards

Understanding this phenomenon requires situating it within both psychological theory and cultural critique. Human behavior operates on the principles of reinforcement: behaviors that are rewarded are repeated. Skinner’s work on operant conditioning showed that people are more likely to repeat behaviors when they receive rewards on an irregular basis. Dating apps make use of this same principle by offering unpredictable matches and responses. This type of reward pattern is considered especially compelling and has also been linked to gambling behavior, which helps explain why swiping can feel so addictive [2]. This principle underpins the mechanics of the swipe loop. Each swipe carries the potential for reward, a match, a message, or a validation of one’s attractiveness, but this reward is unpredictable.

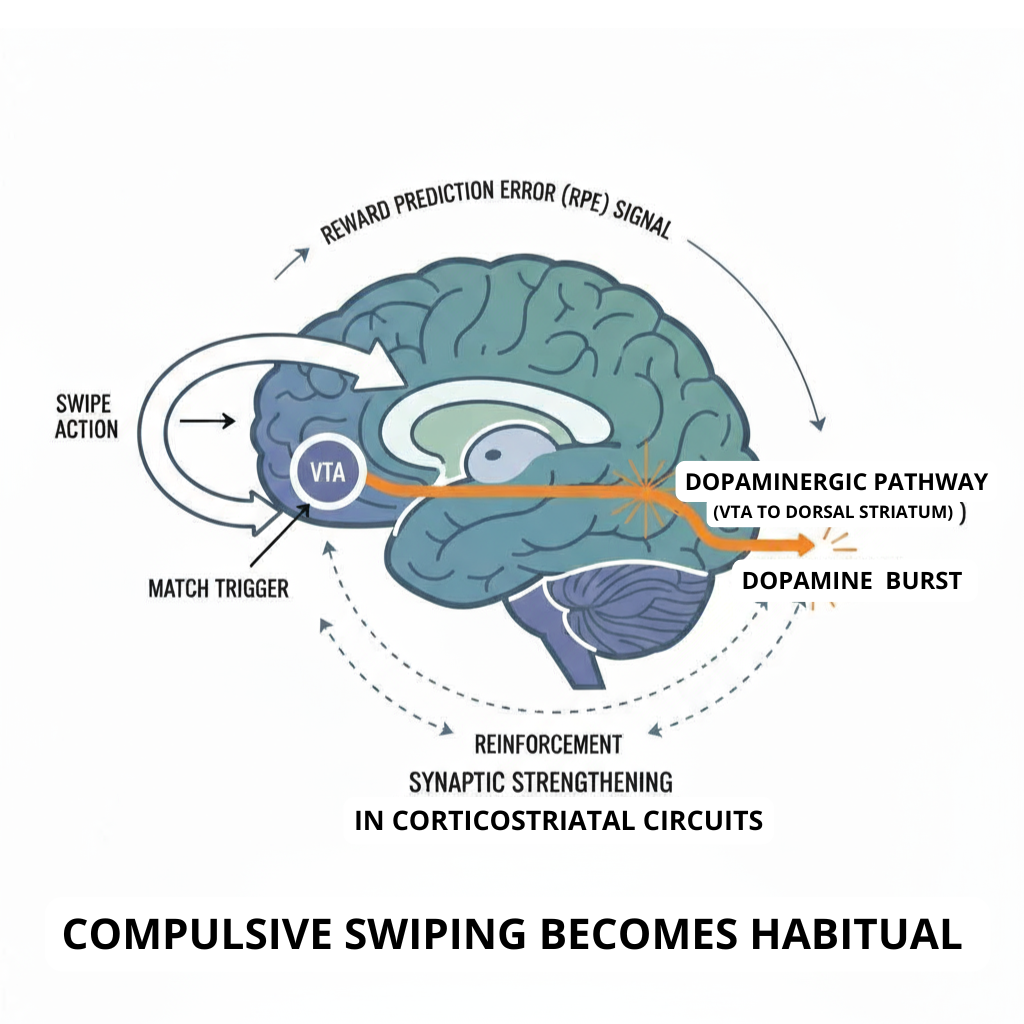

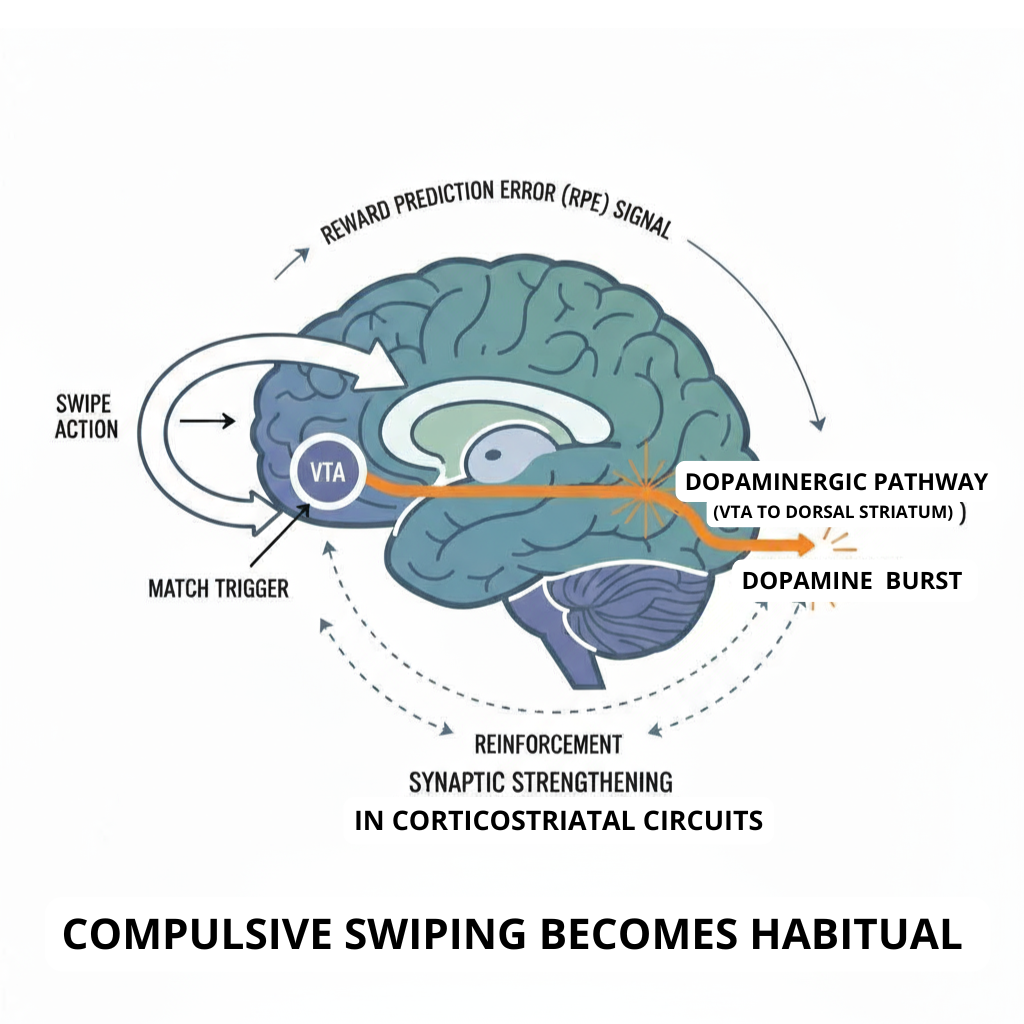

Dopamine in the brain is highly sensitive to surprises; it rises when something positive happens unexpectedly and falls when anticipated rewards don’t appear. Dating apps tap into this system by offering matches and messages on an inconsistent schedule, which strengthens the urge to keep swiping even when the outcomes are often disappointing. When you swipe on a dating app, your brain is running a powerful learning system fueled by dopamine, the brain’s “teaching signal.” The key player here is a small midbrain region called the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA). Think of it as a control center that sends dopamine to other important regions like the striatum (involved in motivation and habit formation) and the cortex (the part that plans and makes decisions) [3,4].

Interestingly, every swipe carries the possibility of a reward, a match, a message, or some form of validation. But because you never know when (or if) that reward will appear, the system becomes especially addictive. When nothing happens, your brain registers the absence of reward. When something unexpected happens (say, you get a match when you weren’t expecting it), the VTA fires off a quick burst of dopamine [5,6].

Neuroscientists call this a reward prediction error (RPE), i.e., the difference between what you expected and what actually happened. These little “surprise bursts” of dopamine are powerful. They don’t just make you feel good in the moment; they teach your brain to repeat the action that led to the reward. Over time, this cycle rewires the brain. At first, swiping is a conscious choice (“I’ll check the app to see who’s out there”). But repeated dopamine bursts strengthen pathways in the corticostriatal circuit, the loop that connects planning, motivation and action. Eventually, swiping shifts from being a thoughtful action to an automatic habit [7,8]. You don’t even think about it anymore; your thumb just does it.

Dating apps are designed to maximise these surprise bursts. By keeping rewards unpredictable (sometimes you match, sometimes you don’t), they mimic the psychology of gambling. This unpredictability makes the loop hard to break, because your brain keeps chasing the next surprise. In short, dating apps tap into ancient reward circuits in the brain. What feels like “just swiping” is actually a neurochemical loop of expectation, surprise, dopamine and habit formation. It’s not just technology, it’s neuroscience in action [8,9].

Description: Illustration showing the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) to dorsal striatum dopaminergic pathway, its role in reward prediction error, and the neural basis of habit formation. The VTA is a key midbrain region with dopaminergic neurons that project to various brain areas, including the cortex and the striatum, forming part of the dopaminergic system involved in reward, motivation, and cognition. (Image generated with Perplexity, inspired by key findings from [7,10-12]. (See references for details on underlying neuroscience.)

The culture of choice overload and disposability

The culture of current dating apps normalises disposability; instead of cultivating meaningful relationships, the user is presented with choice overload where they have an endless stream of potential partners, which creates an illusion of abundance; combined with anonymity of the person you are talking to, this makes users feel and treat others as replaceable; it encourages moving on instantly from one person to another without any explanation, normalising ghosting or cutting off.

Psychologists have discovered that having too many options can make people less happy with their choices. On dating apps, the large number of profiles can lead users to doubt themselves or hesitate to commit. Research on decision-making shows that when people face many options, they often feel less satisfied and are less likely to stick to their decisions. This finding relates directly to dating apps, where the surplus of profiles ironically makes users less willing to invest in any one connection. The endless scroll of profiles creates an atmosphere of unlimited possibilities, which leads to what psychologists call the paradox of choice [13].

While more options might seem advantageous, an excess of choice often produces decision fatigue, anxiety and dissatisfaction with one’s decisions. Iyengar and Leper [14] demonstrated that individuals presented with extensive choices were less likely to commit and less satisfied with their selections. This finding maps directly onto dating apps, where the abundance of profiles paradoxically reduces users’ willingness to invest in any single connection.

Wang [15] notes that the swiping interface strengthens the impression of limitless options, devaluing individual connections and reducing the perceived importance of any single interaction. These systems are designed to reinforce negative behaviours by rewarding users with the convenience of replacing potential partners and avoiding difficult conversations, hence damaging the fabric of trust and empathy in modern dating, leaving more users isolated and anxious. Decision fatigue compounds this problem. Other studies on decision-making suggest that the more choices people have to make, the more mentally drained they become. As their energy depletes, they are more likely to act impulsively or give up altogether. This helps explain why endless swiping often leads to shallow judgments and rushed interactions. On dating apps, endless swiping can exhaust decision-making capacities, leading to superficial judgments, impulsive matches, or disengagement altogether.

Emotional and neurochemical implications

When you know there are thousands of profiles a swipe away, any single person feels less important. Ghosting becomes normalised. Why have a difficult conversation when you can simply vanish and swipe again? This erodes empathy and makes dating feel transactional, like browsing a human catalog. People protect themselves emotionally by keeping things surface-level. This perpetuates a feedback loop in which users feel less responsible for interpersonal outcomes, increasing social isolation and emotional exhaustion. Dating apps don’t merely change how we date, they shift cultural values around connection.

Ghosting has become a key aspect of modern dating culture. Although conflict avoidance and withdrawal from interactions have existed before digital platforms, dating apps worsen these behaviors by lowering accountability and making it easier to find new connections. LeFebvre [16] defines ghosting as ending communication unilaterally and without explanation. In face-to-face situations, this kind of abrupt disengagement often has social repercussions because shared networks create accountability. In online dating, however, the absence of a common community and the many alternative partners lessen these repercussions. Users can easily cut off contact and move on, knowing new matches are available.

Digital interactions like swiping on dating apps primarily engage the brain’s dopamine-based reward system, which thrives on novelty and unpredictable positive feedback, making these platforms highly stimulating and sometimes compulsive for users [17,20]. However, dopamine’s short-term highs are not matched by parallel increases in oxytocin, the neuropeptide central to trust, long-term attachment and emotional security, because oxytocin is most powerfully released through physical touch, eye contact and in-depth, emotionally rich communication, all of which are limited or absent in app-based dating [18-20]. As a result, while dating apps encourage repeated engagement and a search for the next rewarding match, they rarely foster the neurochemical basis for deeper connection and sustained fulfillment, sometimes leaving users feeling emotionally dissatisfied despite frequent interactions [18,20].

Dating app algorithms optimise for user engagement rather than successful connection. Thomas et al. [21] note that these platforms employ tactics such as:

- Curated exposure of profiles to extend time spent on the app.

- Leveraging intermittent reward systems as behavioral triggers.

- Limiting match visibility to keep users hopeful and engaged.

Such practices align with the principles of surveillance capitalism, where users' preferences and behaviors become sources of profit [1]. Moreover, the tendency to prioritise quantity (matches) over quality (meaningful connection) works against user well-being, creating systemic barriers to breaking free from the swipe cycle [22].

Hao Wang [15] points out that swiping interfaces reinforce the sense that there are unlimited options. This abundance can make each individual connection feel less significant and can reduce the value people place on any single relationship.

Another important result of the swipe loop is emotional exhaustion. Users frequently say they feel drained, cynical and hopeless after using dating apps for a long time [23]. Burnout appears in several forms. There is message fatigue, which is the emotional effort involved in starting and maintaining conversations with many partners. Disappointment cycles occur when users repeatedly face unmet expectations as conversations fade or matches disappear. This fits with the Job Demands–Resources model in psychology [24], where emotional demands without enough resources lead to burnout. Dating apps create high emotional demands, including constant evaluation, rejection and uncertainty while not providing the necessary support for resilience.

The irony is that while apps promise connection, their design leads to loneliness and anxiety. Sherry Turkle [25], in her book Alone Together, explains how digital tools can make people feel connected while also leaving them emotionally empty. Dating apps show this contradiction: users have many potential partners but often feel more alone over time. The swipe loop highlights this contradiction; users see potential partners but feel more disconnected.

From a psychological viewpoint, swiping takes advantage of deep-rooted cognitive and emotional processes. The variable-ratio reward schedule works like a slot machine, creating a dopamine-driven urge. This design causes decision fatigue, lowers satisfaction and leads to cycles of craving and exhaustion. Instead of encouraging real connection, the apps reward users for staying in the loop [26].

Breaking the swipe loop and reclaiming connection

Existing dating apps reveal a paradox of our time; they promise connection but often deliver detachment, leaving many users anxious, exhausted and uncertain of what they really want. The problem is not that people ghost, get distracted, or struggle with vulnerability; these issues have always existed in human relationships. The deeper issue is how systemic design choices in these platforms amplify those tendencies, feeding on novelty-seeking instincts, magnifying superficial traits and keeping users trapped in cycles of craving without fulfillment. What looks like abundance quickly becomes scarcity of meaning.

If we are to move beyond this swipe-driven fatigue, the solution lies in redesigning platforms and our approach to them. Apps need to shift incentives away from maximising “time spent” and toward fostering intentional matches, transparency and accountability. Features that slow down swiping, encourage reflection before making decisions and prioritise deeper compatibility over instant validation could help break the addictive loop. Likewise, users can protect their well-being by setting conscious boundaries: limiting time on apps, approaching them with clear intentions and recognising when endless scrolling no longer serves them.

In other words, the answer isn’t abandoning technology altogether but reimagining it so that it works with our psychological and emotional needs, rather than against them. Some emerging platforms are already experimenting with this offering by curated matches, slowing down the pace of interaction, or designing for long-term trust instead of short-term dopamine hits. In doing so, they might begin to change the very chemistry of online dating from a dopamine-driven loop of hope and disappointment to something that genuinely sustains connection, trust and emotional well-being.

References:

[1] Zuboff S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.PublicAffairs; 2019.

[2] Skinner B. Science and Human Behavior.

[3] Schultz W et al. Dopamine neurons and their role in reward mechanisms.Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7(2):191–7.

[4] Volkow ND et al. Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake.Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(1):37–46.

[5] Schultz W. Dopamine reward prediction‑error signalling: a two‑component response.Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2016 Mar;17(3):183‑95.

[6] Keiflin R, Janak PH. Dopamine Prediction Errors in Reward Learning and Addiction: From Theory to Neural Circuitry.Neuron. 2015 Oct 21;88(2):247‑63.

[7] Lipton DM et al. Dorsal Striatal Circuits for Habits, Compulsions and Addictions.Front Syst Neurosci. 2019;13:28.

[8] Bromberg‑Martin ES et al. Dopamine in Motivational Control: Rewarding, Aversive, and Alerting. Neuron.2010;68(5):815–34.

[9] Lerner TN et al. Dopamine, updated: reward prediction error and beyond.Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021;67:123–130.

[10] Malvaez M, Wassum KM. Regulation of habit formation in the dorsal striatum. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences.2017 Nov 21;20:67–74.

[11] Wickens JR et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms in actions and habits.Journal of Neuroscience. 2007 Aug 1;27(31):8181–3.

[12] Graybiel AM, Grafton ST. The striatum: where skills and habits meet.Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015 Aug 1;7(8):a021691.

[13] Schwartz B. The paradox of choice: why more is less.New York: Harper Perennial; 2004 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[14] Iyengar SS, Lepper MR. When choice is demotivating: can one desire too much of a good thing?J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(6):995-1006 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[15] Wang H. Algorithmic colonization of love.Philos Technol. 2020;33(2):1-25 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[16] LeFebvre LE. Phantom lovers: ghosting as a relationship dissolution strategy in the technological age. In: Punyanunt-Carter NM, Wrench JS, editors. Swipe right for love: the impact of social media in modern romantic relationships.Lanham (MD): Lexington Books; 2017. p. 219-236 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[17] Baskerville TA, Douglas AJ. Dopamine and oxytocin interactions Underlying behaviors: potential contributions to behavioral disorders.CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2010 May 6;16(3):e92-123.

[18] Feldman R. The neurobiology of human attachments.Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21(2):80-99 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[19] BetterHelp Editorial Team. Understanding dopamine: dopamine’s love hormones and the brain.BetterHelp; 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[20] Pass C. How dopamine and oxytocin affect our online dating habits.LinkedIn; 2025 May 5 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[21] Thomas MF, Binder A, Stevic A, et al. 99 + matches but a spark ain’t one: adverse psychological effects of excessive swiping on dating apps.Telemat Inform. 2023;78:101949.

[22] Bucher T. The algorithmic imaginary: exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms.Information Communication & Society [Internet]. 2016 Feb 25;20(1):30–44.

[23] Timmermans E, Courtois C. From swiping to casual sex and/or committed relationships: Exploring the experiences of Tinder users.The Information Society [Internet]. 2018 Mar 8;34(2):59–70.

[24] Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout.J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499-512. PMID:11419809.

[25] Turkle S. Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other.New York: Basic Books; 2011 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[26] Strubel J, Petrie TA. Why Tinder is so evilly satisfying.The Conversation; 2017 Apr 11 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

About the author:

Sharvani is a bioinformatics graduate and neuroscience enthusiast passionate about understanding behavior, emotion, and connection. She enjoys exploring how science and technology influence modern relationships. In her free time, she loves watching films and reading. Connect with her on LinkedIn

Trapped in a swipe loop?

One of the questions that has always bothered me is: “Are existing dating apps creating unhealthy behaviours, such as swipe addiction and ghosting, or are they simply escalating the patterns that already existed in human relationships with systemic design?” Some degree of ghosting or dating burnout exists on these apps; however, the systemic design of these dating apps accelerates and magnifies these tendencies. Dating apps thus do not merely reflect natural novelty-seeking tendencies but intensify them through design.

While the impulse to seek novelty is natural, these apps exploit it by designing pathways that channel these impulses into endless swiping without resolution and escalating superficiality over deeper bonds and detachment over a larger scale. Zuboff [1] argues in her broader theory of surveillance capitalism that digital platforms aim to maximise user engagement for profit, often harming individual well-being. Dating apps thus serve a dual function: they offer the prospect of connection while also creating scarcity, novelty and frustration, ensuring users remain active and dependent.

The dopamine-driven swiping loop: Addiction hidden in algorithmic design

The swipe mechanism on dating apps sets up feedback cycles that trigger dopamine release, reinforcing compulsive use. Ironically, while users seek connections, this loop increases loneliness and anxiety. It keeps users in a state of hope, craving validation and connection. Importantly, the algorithms are designed to intentionally keep the users starved, preventing them from easily finding their people or a long term relationship. While the stated purpose of these applications is to create connection, the loop often produces the opposite result: loneliness, anxiety and diminished trust in others. Existing dating apps are not neutral technologies; their algorithms are optimised for engagement, not well being. This optimisation manifests in design choices that withhold matches to sustain hope, prioritise superficial traits over deeper compatibility and perpetuate user reliance on the platform.

Reinforcement and unpredictable rewards

Understanding this phenomenon requires situating it within both psychological theory and cultural critique. Human behavior operates on the principles of reinforcement: behaviors that are rewarded are repeated. Skinner’s work on operant conditioning showed that people are more likely to repeat behaviors when they receive rewards on an irregular basis. Dating apps make use of this same principle by offering unpredictable matches and responses. This type of reward pattern is considered especially compelling and has also been linked to gambling behavior, which helps explain why swiping can feel so addictive [2]. This principle underpins the mechanics of the swipe loop. Each swipe carries the potential for reward, a match, a message, or a validation of one’s attractiveness, but this reward is unpredictable.

Dopamine in the brain is highly sensitive to surprises; it rises when something positive happens unexpectedly and falls when anticipated rewards don’t appear. Dating apps tap into this system by offering matches and messages on an inconsistent schedule, which strengthens the urge to keep swiping even when the outcomes are often disappointing. When you swipe on a dating app, your brain is running a powerful learning system fueled by dopamine, the brain’s “teaching signal.” The key player here is a small midbrain region called the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA). Think of it as a control center that sends dopamine to other important regions like the striatum (involved in motivation and habit formation) and the cortex (the part that plans and makes decisions) [3,4].

Interestingly, every swipe carries the possibility of a reward, a match, a message, or some form of validation. But because you never know when (or if) that reward will appear, the system becomes especially addictive. When nothing happens, your brain registers the absence of reward. When something unexpected happens (say, you get a match when you weren’t expecting it), the VTA fires off a quick burst of dopamine [5,6].

Neuroscientists call this a reward prediction error (RPE), i.e., the difference between what you expected and what actually happened. These little “surprise bursts” of dopamine are powerful. They don’t just make you feel good in the moment; they teach your brain to repeat the action that led to the reward. Over time, this cycle rewires the brain. At first, swiping is a conscious choice (“I’ll check the app to see who’s out there”). But repeated dopamine bursts strengthen pathways in the corticostriatal circuit, the loop that connects planning, motivation and action. Eventually, swiping shifts from being a thoughtful action to an automatic habit [7,8]. You don’t even think about it anymore; your thumb just does it.

Dating apps are designed to maximise these surprise bursts. By keeping rewards unpredictable (sometimes you match, sometimes you don’t), they mimic the psychology of gambling. This unpredictability makes the loop hard to break, because your brain keeps chasing the next surprise. In short, dating apps tap into ancient reward circuits in the brain. What feels like “just swiping” is actually a neurochemical loop of expectation, surprise, dopamine and habit formation. It’s not just technology, it’s neuroscience in action [8,9].

Description: Illustration showing the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) to dorsal striatum dopaminergic pathway, its role in reward prediction error, and the neural basis of habit formation. The VTA is a key midbrain region with dopaminergic neurons that project to various brain areas, including the cortex and the striatum, forming part of the dopaminergic system involved in reward, motivation, and cognition. (Image generated with Perplexity, inspired by key findings from [7,10-12]. (See references for details on underlying neuroscience.)

The culture of choice overload and disposability

The culture of current dating apps normalises disposability; instead of cultivating meaningful relationships, the user is presented with choice overload where they have an endless stream of potential partners, which creates an illusion of abundance; combined with anonymity of the person you are talking to, this makes users feel and treat others as replaceable; it encourages moving on instantly from one person to another without any explanation, normalising ghosting or cutting off.

Psychologists have discovered that having too many options can make people less happy with their choices. On dating apps, the large number of profiles can lead users to doubt themselves or hesitate to commit. Research on decision-making shows that when people face many options, they often feel less satisfied and are less likely to stick to their decisions. This finding relates directly to dating apps, where the surplus of profiles ironically makes users less willing to invest in any one connection. The endless scroll of profiles creates an atmosphere of unlimited possibilities, which leads to what psychologists call the paradox of choice [13].

While more options might seem advantageous, an excess of choice often produces decision fatigue, anxiety and dissatisfaction with one’s decisions. Iyengar and Leper [14] demonstrated that individuals presented with extensive choices were less likely to commit and less satisfied with their selections. This finding maps directly onto dating apps, where the abundance of profiles paradoxically reduces users’ willingness to invest in any single connection.

Wang [15] notes that the swiping interface strengthens the impression of limitless options, devaluing individual connections and reducing the perceived importance of any single interaction. These systems are designed to reinforce negative behaviours by rewarding users with the convenience of replacing potential partners and avoiding difficult conversations, hence damaging the fabric of trust and empathy in modern dating, leaving more users isolated and anxious. Decision fatigue compounds this problem. Other studies on decision-making suggest that the more choices people have to make, the more mentally drained they become. As their energy depletes, they are more likely to act impulsively or give up altogether. This helps explain why endless swiping often leads to shallow judgments and rushed interactions. On dating apps, endless swiping can exhaust decision-making capacities, leading to superficial judgments, impulsive matches, or disengagement altogether.

Emotional and neurochemical implications

When you know there are thousands of profiles a swipe away, any single person feels less important. Ghosting becomes normalised. Why have a difficult conversation when you can simply vanish and swipe again? This erodes empathy and makes dating feel transactional, like browsing a human catalog. People protect themselves emotionally by keeping things surface-level. This perpetuates a feedback loop in which users feel less responsible for interpersonal outcomes, increasing social isolation and emotional exhaustion. Dating apps don’t merely change how we date, they shift cultural values around connection.

Ghosting has become a key aspect of modern dating culture. Although conflict avoidance and withdrawal from interactions have existed before digital platforms, dating apps worsen these behaviors by lowering accountability and making it easier to find new connections. LeFebvre [16] defines ghosting as ending communication unilaterally and without explanation. In face-to-face situations, this kind of abrupt disengagement often has social repercussions because shared networks create accountability. In online dating, however, the absence of a common community and the many alternative partners lessen these repercussions. Users can easily cut off contact and move on, knowing new matches are available.

Digital interactions like swiping on dating apps primarily engage the brain’s dopamine-based reward system, which thrives on novelty and unpredictable positive feedback, making these platforms highly stimulating and sometimes compulsive for users [17,20]. However, dopamine’s short-term highs are not matched by parallel increases in oxytocin, the neuropeptide central to trust, long-term attachment and emotional security, because oxytocin is most powerfully released through physical touch, eye contact and in-depth, emotionally rich communication, all of which are limited or absent in app-based dating [18-20]. As a result, while dating apps encourage repeated engagement and a search for the next rewarding match, they rarely foster the neurochemical basis for deeper connection and sustained fulfillment, sometimes leaving users feeling emotionally dissatisfied despite frequent interactions [18,20].

Dating app algorithms optimise for user engagement rather than successful connection. Thomas et al. [21] note that these platforms employ tactics such as:

- Curated exposure of profiles to extend time spent on the app.

- Leveraging intermittent reward systems as behavioral triggers.

- Limiting match visibility to keep users hopeful and engaged.

Such practices align with the principles of surveillance capitalism, where users' preferences and behaviors become sources of profit [1]. Moreover, the tendency to prioritise quantity (matches) over quality (meaningful connection) works against user well-being, creating systemic barriers to breaking free from the swipe cycle [22].

Hao Wang [15] points out that swiping interfaces reinforce the sense that there are unlimited options. This abundance can make each individual connection feel less significant and can reduce the value people place on any single relationship.

Another important result of the swipe loop is emotional exhaustion. Users frequently say they feel drained, cynical and hopeless after using dating apps for a long time [23]. Burnout appears in several forms. There is message fatigue, which is the emotional effort involved in starting and maintaining conversations with many partners. Disappointment cycles occur when users repeatedly face unmet expectations as conversations fade or matches disappear. This fits with the Job Demands–Resources model in psychology [24], where emotional demands without enough resources lead to burnout. Dating apps create high emotional demands, including constant evaluation, rejection and uncertainty while not providing the necessary support for resilience.

The irony is that while apps promise connection, their design leads to loneliness and anxiety. Sherry Turkle [25], in her book Alone Together, explains how digital tools can make people feel connected while also leaving them emotionally empty. Dating apps show this contradiction: users have many potential partners but often feel more alone over time. The swipe loop highlights this contradiction; users see potential partners but feel more disconnected.

From a psychological viewpoint, swiping takes advantage of deep-rooted cognitive and emotional processes. The variable-ratio reward schedule works like a slot machine, creating a dopamine-driven urge. This design causes decision fatigue, lowers satisfaction and leads to cycles of craving and exhaustion. Instead of encouraging real connection, the apps reward users for staying in the loop [26].

Breaking the swipe loop and reclaiming connection

Existing dating apps reveal a paradox of our time; they promise connection but often deliver detachment, leaving many users anxious, exhausted and uncertain of what they really want. The problem is not that people ghost, get distracted, or struggle with vulnerability; these issues have always existed in human relationships. The deeper issue is how systemic design choices in these platforms amplify those tendencies, feeding on novelty-seeking instincts, magnifying superficial traits and keeping users trapped in cycles of craving without fulfillment. What looks like abundance quickly becomes scarcity of meaning.

If we are to move beyond this swipe-driven fatigue, the solution lies in redesigning platforms and our approach to them. Apps need to shift incentives away from maximising “time spent” and toward fostering intentional matches, transparency and accountability. Features that slow down swiping, encourage reflection before making decisions and prioritise deeper compatibility over instant validation could help break the addictive loop. Likewise, users can protect their well-being by setting conscious boundaries: limiting time on apps, approaching them with clear intentions and recognising when endless scrolling no longer serves them.

In other words, the answer isn’t abandoning technology altogether but reimagining it so that it works with our psychological and emotional needs, rather than against them. Some emerging platforms are already experimenting with this offering by curated matches, slowing down the pace of interaction, or designing for long-term trust instead of short-term dopamine hits. In doing so, they might begin to change the very chemistry of online dating from a dopamine-driven loop of hope and disappointment to something that genuinely sustains connection, trust and emotional well-being.

References:

[1] Zuboff S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.PublicAffairs; 2019.

[2] Skinner B. Science and Human Behavior.

[3] Schultz W et al. Dopamine neurons and their role in reward mechanisms.Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7(2):191–7.

[4] Volkow ND et al. Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake.Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(1):37–46.

[5] Schultz W. Dopamine reward prediction‑error signalling: a two‑component response.Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2016 Mar;17(3):183‑95.

[6] Keiflin R, Janak PH. Dopamine Prediction Errors in Reward Learning and Addiction: From Theory to Neural Circuitry.Neuron. 2015 Oct 21;88(2):247‑63.

[7] Lipton DM et al. Dorsal Striatal Circuits for Habits, Compulsions and Addictions.Front Syst Neurosci. 2019;13:28.

[8] Bromberg‑Martin ES et al. Dopamine in Motivational Control: Rewarding, Aversive, and Alerting. Neuron.2010;68(5):815–34.

[9] Lerner TN et al. Dopamine, updated: reward prediction error and beyond.Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021;67:123–130.

[10] Malvaez M, Wassum KM. Regulation of habit formation in the dorsal striatum. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences.2017 Nov 21;20:67–74.

[11] Wickens JR et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms in actions and habits.Journal of Neuroscience. 2007 Aug 1;27(31):8181–3.

[12] Graybiel AM, Grafton ST. The striatum: where skills and habits meet.Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015 Aug 1;7(8):a021691.

[13] Schwartz B. The paradox of choice: why more is less.New York: Harper Perennial; 2004 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[14] Iyengar SS, Lepper MR. When choice is demotivating: can one desire too much of a good thing?J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(6):995-1006 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[15] Wang H. Algorithmic colonization of love.Philos Technol. 2020;33(2):1-25 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[16] LeFebvre LE. Phantom lovers: ghosting as a relationship dissolution strategy in the technological age. In: Punyanunt-Carter NM, Wrench JS, editors. Swipe right for love: the impact of social media in modern romantic relationships.Lanham (MD): Lexington Books; 2017. p. 219-236 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[17] Baskerville TA, Douglas AJ. Dopamine and oxytocin interactions Underlying behaviors: potential contributions to behavioral disorders.CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2010 May 6;16(3):e92-123.

[18] Feldman R. The neurobiology of human attachments.Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21(2):80-99 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[19] BetterHelp Editorial Team. Understanding dopamine: dopamine’s love hormones and the brain.BetterHelp; 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[20] Pass C. How dopamine and oxytocin affect our online dating habits.LinkedIn; 2025 May 5 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[21] Thomas MF, Binder A, Stevic A, et al. 99 + matches but a spark ain’t one: adverse psychological effects of excessive swiping on dating apps.Telemat Inform. 2023;78:101949.

[22] Bucher T. The algorithmic imaginary: exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms.Information Communication & Society [Internet]. 2016 Feb 25;20(1):30–44.

[23] Timmermans E, Courtois C. From swiping to casual sex and/or committed relationships: Exploring the experiences of Tinder users.The Information Society [Internet]. 2018 Mar 8;34(2):59–70.

[24] Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout.J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499-512. PMID:11419809.

[25] Turkle S. Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other.New York: Basic Books; 2011 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

[26] Strubel J, Petrie TA. Why Tinder is so evilly satisfying.The Conversation; 2017 Apr 11 [cited 2025 Dec 09].

About the author:

Sharvani is a bioinformatics graduate and neuroscience enthusiast passionate about understanding behavior, emotion, and connection. She enjoys exploring how science and technology influence modern relationships. In her free time, she loves watching films and reading. Connect with her on LinkedIn